“After I delivered, I went in for my six-week postpartum visit to meet with my doctor. And it somehow came up in conversation that I was part of this suit that was going on.

And she looked at me and she said, ‘well, what’s the big deal?

I mean, you ended up pregnant.’”

~Esha (patient)

Welcome back to my analysis of the last episode of The Retrievals - a podcast about women’s pain from This American Life and The New York Times.

The podcast follows the case of women treated at Yale Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Clinic, where a nurse stole fentanyl meant to sedate patients for a painful fertility procedure. Today, I explore the last episode of the series exploring women's pain, opioids & ethical care.

I’m an anesthesiologist (sedation expert), an ethicist, and a woman. I’m sharing my reflections on every episode of The Retrievals for you on Poppies & Propofol.

I started writing this post in August when the episode came out. I am still figuring out how to capture the unfinishedness of the show. Susan Barton and her team’s work caught the story beautifully, but these patients’ struggles are far from over.

In a more profound sense, the unfinishedness is in no small part because the overall culture of medicine isn’t changing fast enough to prevent this from happening to more women and minoritized patients.

If you missed my analysis of previous episodes, you can read them here: 1 - The Patients, 2 - The Nurse, 3 - The Sentence, and 4 - The Clinic.

If you haven’t listened to Episode 5 yet (released on August 3, 2023), here’s an auto-generated transcript and a link to The Outcomes:

In episode 4, we learned about the clinic, whose environment facilitated not only Donna’s medication diversion but also the systematic dismissal of women’s pain.

In the last episode - Episode 5, we learn more about the outcomes of the scandal.

What health outcomes matter?

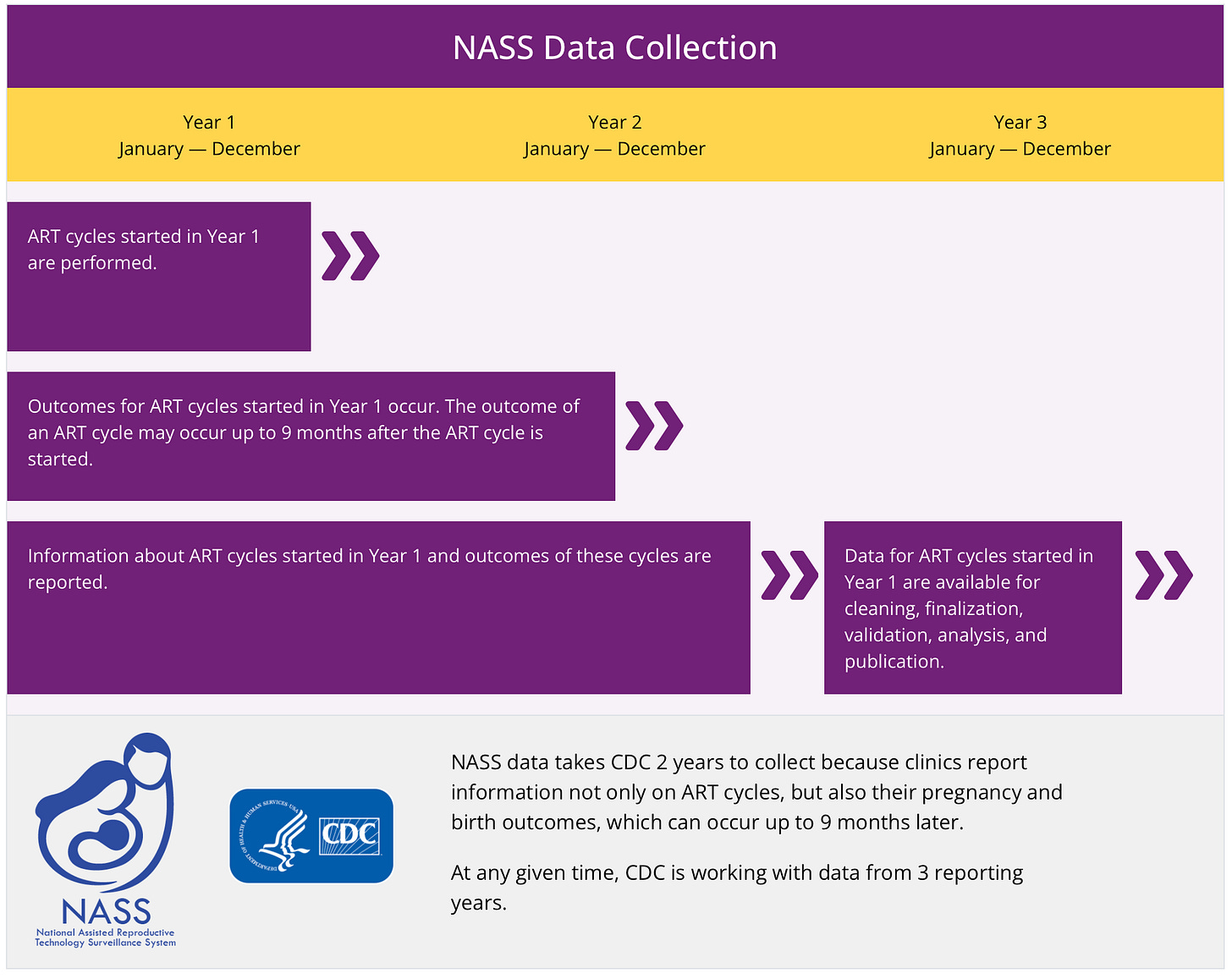

In healthcare, we measure various health outcomes to assess what’s working well and what isn’t in a complex environment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) monitor fertility outcomes in the National Assistive Reproductive Technology Surveillance System (NASS).

Patients can look at the “success” data from a clinic and determine where to go, how far to drive, and who to see for care based on this snapshot about a fertility clinic.

NASS data include—

Patient demographics.

Patient obstetrical and medical history.

Parental infertility diagnosis.

Clinical parameters of the ART procedure.

Information regarding resultant pregnancies and births.

The “most relevant medical outcome measures” in value-based fertility care are time to pregnancy (TTP) and ongoing pregnancy rate (OPR). These are proxy for the live birth rate - the rate at which babies were born. With this perspective, it’s no surprise Esha’s physicians asked “what’s the big deal [that you were traumatized by your egg retrieval]?” Esha got pregnant - a commonly measurable outcome - and therefore, the physician seems to reason, that the outcome was successful.

Patient Experience

Despite patient experience being a critical aspect of healthcare, Esha’s traumatic experience wasn’t given much weight. The lack of collection and value for patients’ experiences is a problem.

In 2010, a group worked to create a survey to measure patient-centeredness in fertility care. They found that “Honesty and clearness on what to expect from fertility care” were very important to patients. They studied a Dutch population, but there’s not good reason to believe patients at Yale would not value honesty and clarity.

And yet, Yale’s patients didn’t get honesty or clarity. They got lies, deceit, poor care, and then gaslighting from their doctors and the entire Yale health system.

Journey vs. Destination

In the clinic, the patients’ pain was dismissed and their discussion of it afterwards trivialized. Their desire for accountability ignored. If they reached the destination (pregnancy), then their journeys didn’t matter at all.

The Measure of Trauma

The danger of measurable outcomes - people only see the measured ones. We don’t see the impact of the unmeasured outcomes. We won’t see the connections.

One thing we miss in excluding data about patients’ experiences is how their experience - especially a profoundly negative experience - may impact other measured outcomes.

Were fewer eggs collected because the retrieval process was too painful? Did doctors (appropriately) give up because stabbing a long needle around in a moving patient’s vagina was unsafe? How many patients never went back for subsequent, recommended retrievals due to fear? Fewer eggs alone will impact fertility outcomes - fewer eggs to make embryos, fewer embryos to assess for potential implantation in the uterus, fewer opportunities to make a baby.

Additionally, to what degree did the acute stress of egg retrieval and the chronic stress that followed play in the measured outcomes? Infertility alone is a huge source of stress, and one study in the 1990’s found women who experience infertility have depression and anxiety similar to women diagnosed with cancer. Stress hormones, like cortisol, disrupt signaling between the brain and the ovaries, impacting menstruation and ovulation. Were these patients less likely to become pregnant overall?

Having a child after this and being pregnant and going to these sentencing hearings, that’s something I haven’t even talked about. Is being pregnant and going – and how much of this did I actually, again, want my body to absorb while I was pregnant?

- Leah

Beyond the acute stress of these patients’ egg retrieval procedures, the interviews reveal women with signs of post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic stress. Years later, they are still suffering. Yale could have buffered against these negative outcomes by taking women and their complaints of pain seriously, but instead, they betrayed their patients.

Loss of Trust

Women interviewed in The Retrievals shared a loss in trust in the healthcare system is:

“The negative downstream effect is just a deep mistrust of the medical setting. Where I work, by the way.” - Katie

“To trust people with something as priceless as your child or whatever it is you’re doing to bring a child into this world and to lose that trust, it’s not something you ever get over.” - Camise

“And I felt really distrustful about the other providers that I would be seeing at Yale and when it came to them touching my body or coming near me.” - Esha

These predictable consequences of bias against women’s pain lead to poorer health outcomes. Why would women feel safe trusting clinicians who didn’t believe them.

Physicians describe men with chronic pain are described as stoic and brave, but women as emotional and hysterical. Women are accused of exaggerating their pain compared to men. Women’s health isn’t studied as much as men’s, leading to a vicious cycle where women’s health is poorly understood and because it’s poorly understood, treated as less than real.

Beyond these systematic biases, women who were writhing in pain in an infertility clinic in front of at least one doctor and one nurse were not treated as though their experience was valid. They were blamed for their out of control pain, rather than folks in the clinic looking into the factors that facilitated such pain.

When women’s experiences aren’t treated as valid and trustworthy, women learn not to trust clinicians.

Art of Sedation

As an anesthesiologists, I took note of how many anesthesiologists were left to navigate the after effects of these patients’ experiences - either for their next egg retrieval or for delivery of their baby.

“And he was talking to me about, these are the medications I’m going to give you. And he’s like, and you’ll most likely be asleep. But there’s a chance that you could be awake. And then I was like, wait, wait, what? And so I started crying.

And I just basically told him, I was part of that situation. And he was so caring and understanding. He was like, I will make sure that you’re not awake for anything. I will be on top of it, and I will make sure that you’re given everything so that you don’t wake up or know what’s happening.”

- Laura

So much of what I do when meeting patients involves talking with them about their experiences and expectations so we can get on the same page about what will happen and so I can help alleviate their worries as much as possible.

The anesthesiologist came up to me, and it was this young guy. And said to me, OK, here’s your options. And was talking about a epidural and if we had to do anesthesia and this and that…

I was calm through the entire thing. But the minute he said anesthesia, I looked at my husband in pure panic and started crying. So it really had an effect on me. It still has an effect on me whenever I come across things when it comes to Yale.

- Esha

These two patients were lucky to have subsequent doctors who took their concerns seriously. Not every anesthesiologists would have. We suffer the same biases as everyone else in society.

Unanswered questions

I’ve waited to write my last analysis of The Retrievals, in part because there are so many unanswered questions: how was this clinic so poorly supervised? What conditions contributed to a staff that didn’t recognize or report drug diversion for so long? What group of people at Yale made the decision to undermine and dismiss patient’s complaints of untreated pain? Why didn’t they make the connection between increasing reports of pain and drug diversion? Who was supposed to look at the big picture?

Lawsuits against Yale are far from over. Plaintiffs cared for in the Yale Long Warf REI facility claim they discovered they may have been victims because of The Retrievals podcast. Yale hadn’t notified patients broadly about the impact.

New complaints suggest Yale purposefully prevented patients from learning about untreated pain due to fentanyl diversion.

It’s frustrating to see how an organization systematically betrayed its patients and then refuses to take meaningful steps towards accountability and restorative justice.

Thank you for reading my analysis of The Retrievals podcast.

Thanks for reading! I’ll keep an eye and ear out for further developments in the story and keep you posted.

What did you think of the show? Send me your thoughts or drop them in the comments.

This is so important.

This conversation about listening to patients, believing them, must continue. Suicide is way up in chronic pain community.

Thank you so much.

I’m so sorry these women went through this. I’m sorry for everyone that went through this.