The last time I used physostigmine for a patient was probably the very last time ever.

The small-but-mighty molecule has been an essential resource for me to treat patients with severe, hard-to-treat post-anesthesia delirium - a disturbing and sometimes dangerous side effect some patients experience after exposure to anesthesia.

Why won’t I ever see this magical little drug ever again?

The only company that made it went out of business.

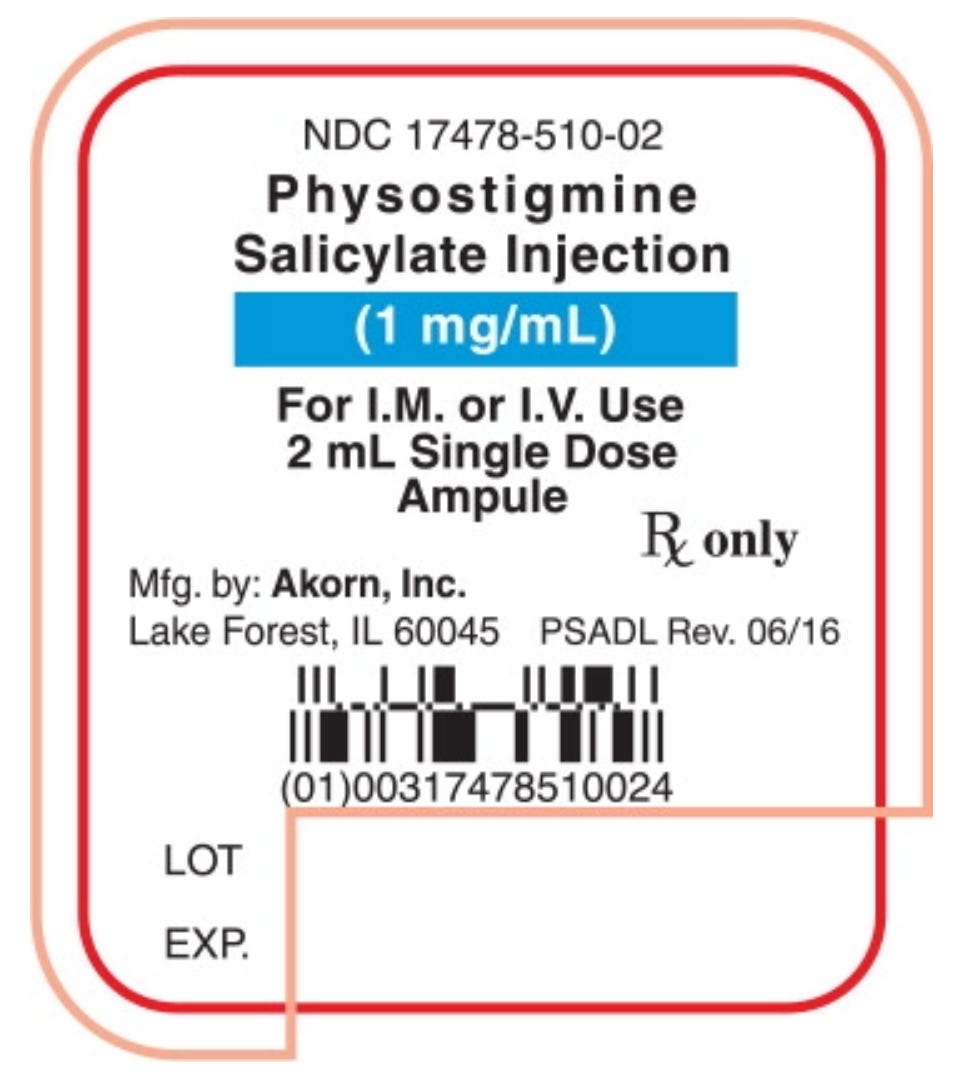

Akorn Operating Co., a drug maker in Gurnee, Illinois, made 100% of the nation's supply of physostigmine salicylate injection and shut down all operations in February 2023. Akorn was also the sole maker of three other drugs: calcitriol injection, alfentanil injection, and dimercaprol injection.

All four drugs are gone forever unless another company decides to make them.

So, dear Poppy & Propofol reader, please indulge me as I mourn the loss of physostigmine and nerd out on a really, really cool ancient botanical drug.

An Agitation Antidote?

In my anesthesiology training, I only used physostigmine once while working with a seasoned anesthesiologist. We gave it just before waking up an elderly patient after brain surgery. The idea was that it would help the patient wake up more quickly. But since I didn’t see the drug in action any other time, I didn’t really understand how powerful it could be.

When I started working with kids and young adults with complex delirium after surgery, I re-discovered this magical delirium antidote.

A surgical colleague asked me to evaluate a patient with a history of profound agitation and delirium in the recovery room after anesthesia. He injured himself and one of his nurses. Seasoned recovery room nurses insisted the patient was doing these things on purpose. Unfortunately, while the patient appeared “awake” after surgery, he would yell, scream, and try to hit the nurses and his parents.

This would last for hours.

But the patient had no memory of these events. Chatting with him in his hospital room, he was quiet and sweet. Because he couldn’t remember the events, he couldn’t tell me if he had other symptoms that might provide clues.

He wasn’t a “violent” or “aggressive” person - something patients are often labeled after they’ve hurt a healthcare worker. His parents could tell that he was being treated like a dangerous person and that didn’t fit with their smart, funny kid. He had a medical condition that meant he’d need many more anesthetics.

We needed a plan.

How could we keep him and the healthcare workers caring for him safe from injury?

I did a deep dive into his medical chart, reviewing records from multiple hospitals. There was no clear connection between other medications, like steroid bursts or other changes in disease management. The reaction didn’t happen every single time he was exposed to anesthesia but happened frequently enough that I suspected a connection.

In my literature search, I came across a paper “Prophylactic Physostigmine for Extreme and Refractory Adult Emergence Delirium, Aimed at Increasing Patient Safety and Reducing Health Care Workplace Violence: A Case Report” written by Dr. David Gutman and colleagues at the Medical University of South Carolina.

They described a nearly identical patient case and effectively treated them with physostigmine. I reached out to the author to compare cases and approaches. I did a bunch more research to familiarize myself with previous studies on physostigmine and anesthesia.

Could this be a case of central anticholinergic syndrome (CAS)?

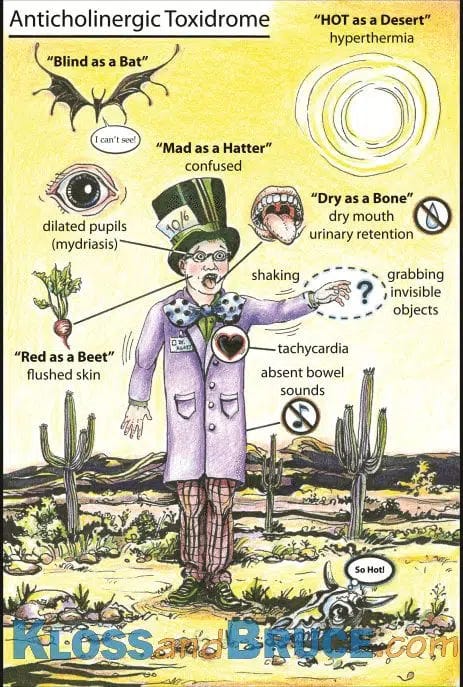

In medical school, we learned the mnemonic for central anticholinergic syndrome, "red as a beet, dry as a bone, blind as a bat, mad as a hatter, hot as a hare, and full as a flask."

Dr. Brian Kloss has a flashcard to visualize CAS symptoms, or “anticholinergic toxidrome.” (Sometimes also called “antimuscarinic toxicity”).

I learned about the obvious signs of CAS, but by the time I was in residency, the idea of post-op delirium as a manifestation of patients potentially not having enough acetylcholine to wake up properly must have fallen out of favor. We certainly weren’t using physostigmine for delirious patients.

I reached out to my residency classmates, and I seemed to be the only one that had ever used it in our training.

After general anesthesia, the incidence of CAS has been reported to be 1%–9%!

CAS can lead to agitation (including seizures, restlessness, hallucinations, and disorientation) or depression (symptoms like stupor, coma, and slow breathing). The syndrome may be induced by anticholinergic drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) - like atropine or scopolamine. But CAS has also been seen after using many other anesthesia medications: opiates (morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone), benzodiazepines (midazolam), butyrophenones (haloperidol), ketamine, cimetidine (for gastric acid), etomidate, propofol, nitrous oxide, and anesthetic gasses.

I couldn’t help but be a little embarrassed that I didn’t know much about the prevalence of the condition from many of the drugs I use every day.

CAS is a diagnosis of exclusion, so you only really know you got the diagnosis correct when physostigmine fixes it.

A Pretty Darn Magical Delirium Antidote

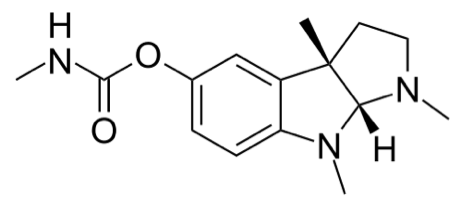

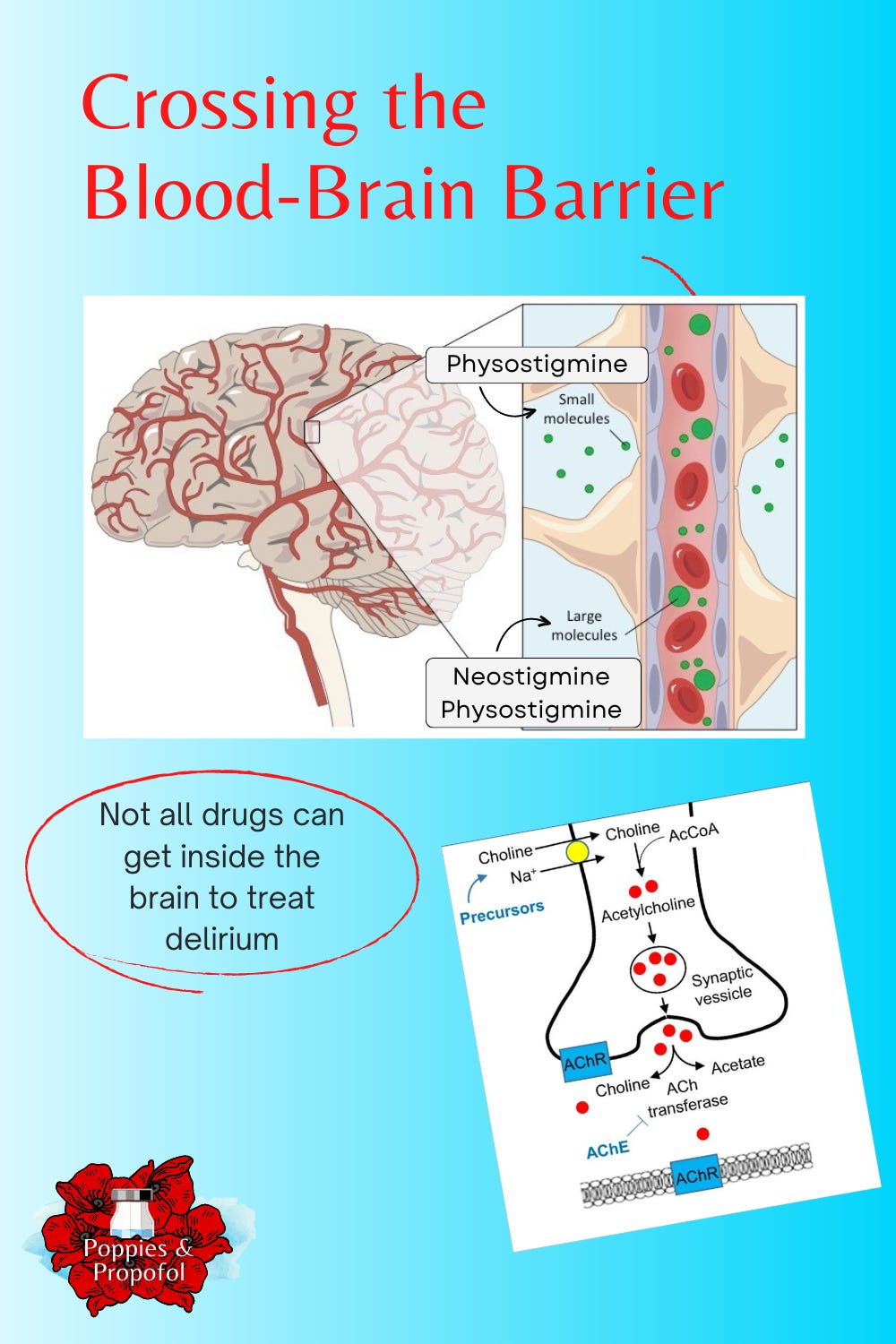

Physostigmine acts on the nervous system, influencing communication between the nerves, organs, and muscles, contributing to both its toxic side effects and its uses. It’s a small molecule that can easily cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) - making it useful for central (brain) and peripheral nerves. (Related drugs, like neostigmine and pyridostigmine, have bigger molecular structures and can’t cross the BBB.)

Physostigmine crosses the BBB very easily, reversing the central toxic effects of anticholinergic medications and emergence delirium: anxiety, delirium, disorientation, hallucinations, hyperactivity, and seizures.

It works very quickly (within 2 minutes) and doesn’t last that long (about 15 minutes). Because of the quick onset, if you’re worried about CAS, you can diagnose it very quickly. It’s also fully metabolized in 1-2 hours.

Physostigmine works on the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest) by inhibiting the enzyme cholinesterase from breaking down acetylcholine. This means there is more acetylcholine around longer to send messages between nerves.

Calabar Beans: The Lie Detector Legume

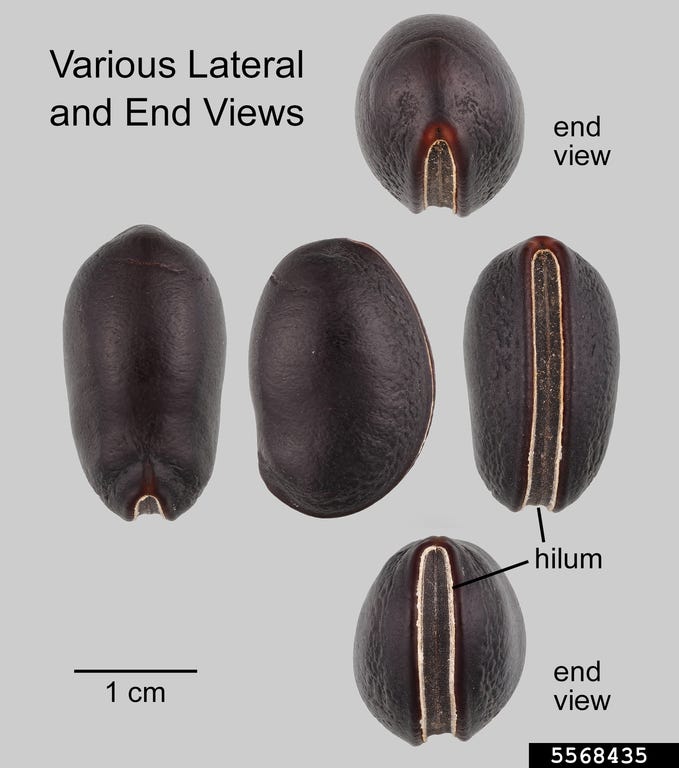

Physostigmine is extracted from the Calabar bean (AKA chop nut, ordeal bean, or lie detector bean). Physostigma venenosum is a climbing, perennial legume indigenous to the coastal area of southeastern Nigeria known as Calabar. Unlike familiar legumes, like peanuts, sweet peas, and garbanzo beans, the dark chocolate-colored Calabar beans are poisonous to humans.

The beans were once used as an ordeal poison. People accused of witchcraft or other crimes would be required to eat the beans, which were only thought to affect guilty people. If they died, they were guilty. If they didn’t die, they might be innocent, but might still be enslaved.

It was… an ordeal.

With processing, Calabar beans can be transformed into a powerful toxin and an antidote against other toxins, like Atropa belladonna (used to make atropine).

What was physostigmine used for?

In 1862, Thomas Fraser told his friend Argyll Robertson, a young Edinburgh ophthalmologist, about physostigmine to constrict the pupil of the eye. Over time, it became the medication most commonly used to manage and treat glaucoma and anticholinergic toxicity. Physostigmine could also be used to reverse neuromuscular blocking medications used in surgery.

In the 1960s and 1970s, physostigmine also became a popular treatment for undifferentiated delirium - delirium when we didn’t know what caused it. But after a few reported deaths from treating patients who had taken overdoses with tricyclic antidepressants, physicians understandably stopped using physostigmine quite as liberally.

Other medications with fewer (or at least different) side effects took over some of physostigmine’s previous uses. While better drugs emerged for glaucoma and reversing muscle relaxant medications, better drugs didn’t materialize for controlling anticholinergic agitation and delirium.

For my patient with emergence agitation - it was like a magic antidote. They woke up feeling like themselves - no outbursts, no confusion.

Below you can watch a video using physostigmine to treat an anticholinergic overdose in a toddler (de-identified). In the video, they have to ask two additional hospitals to provide physostigmine because it was already on shortage.

A Physostigmine-Free Future

My patient’s condition was drastically improved with physostigmine treatment. His episodes of post-operative delirium with hitting and screaming did not re-emerge. For his parents, this was like magic. For the nurses who had labeled him “aggressive,” it was clear the behavior wasn’t on purpose, and was literally caused by the drugs we use every day.

So I am truly bummed that I won’t have access to physostigmine - probably ever again.

Unfortunately, there are no great alternatives to physostigmine. There are other drugs like haloperidol, but if the problem is acetylcholine, why would I use a dopamine blocker? In fact, haloperidol can exacerbate CAM. Benzodiazepines have been shown to be less effective than physostigmine - and again, can be the cause of the condition.

Even for the other drugs that can technically be used for delirium, most of those are also subject to frequent shortages. This study showed not only persistent shortages of drugs to treat anticholinergic (aka antimuscarinic) delirium, but multiple simultaneous shortages.

It’s even harder to find any effective substitute.

Until I can find a better solution for my highest-risk patients, I’m trying out rivastigmine (brand name Exelon) - a medication similar to physostigmine to help Alzheimer’s patients improve memory. Unfortunately, it’s only available orally or as a transdermal skin patch. The oral version is not ideal to give during anesthesia, and it’s even harder to give to a delirious patient.

We don’t like to use cholinesterase inhibitors before anesthesia because they can negatively impact our ability to use other peripheral acetylcholine drugs, like muscle relaxant medications needed to place breathing tubes safely. Patches might be helpful in the post-operative period, but will take a while to be absorbed through the skin to start working. There is a possibility of a rivastigmine nasal spray being available in the future, but it will likely be many years before it’s available in America.

Once again I am amazed at your knowledge! And I learned something new again today😊