Happy Ether Day 2021! (Also known as World Anesthesia Day!)

I can’t think of a better way to kick off this newsletter about my work as an anesthesiologist and ethicist than with a post about the history of anesthesiology!

Being an anesthesiologist with the knowledge and resources to obliterate consciousness and minimize/eliminate pain is something I take for granted every single day. It is incredibly stressful to hear people crying and in pain, and my experience as an observer is nothing compared to the patient’s experience. This passion to treat pain and anxiety drove me to a specialty where I could make a difference in this critical part of surgical care. Unfortuantley, there are many people throughout the world who lack access to anesthesia. Groups like the World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists work to promote access across the world.

Just imagining surgery before anesthesia terrifies me. I gave myself stitches once without access to numbing medication and it is not something I recommend. Before the rise of anesthesia, surgeons had to cut and sew with lighting speed to operate on conscious patients, who writhed and screamed as they were tortured, ostensibly for their own good. Physical pain doesn’t exist in a vaccum, it’s strongly associated with emotional responses: anxiety, dread, and fear. Those emotions don’t disappear with healing wounds, and patients can suffer severe traumatic emotions for the rest of their lives. Surgery was so brutal, so monstrous, that some people chose death over any attempt at surgery. IN 1824, one anonymous correspondent described it like this a then new journal called The Lancet:

“Feverishly heated, and frequently very much exhausted by his previous sufferings, every additional moment, at this dreadful crisis, becomes to him an hour, and every additional moment that he continues under the torture of the different instruments, diminishes the chance of success and … increases the danger of his life.”

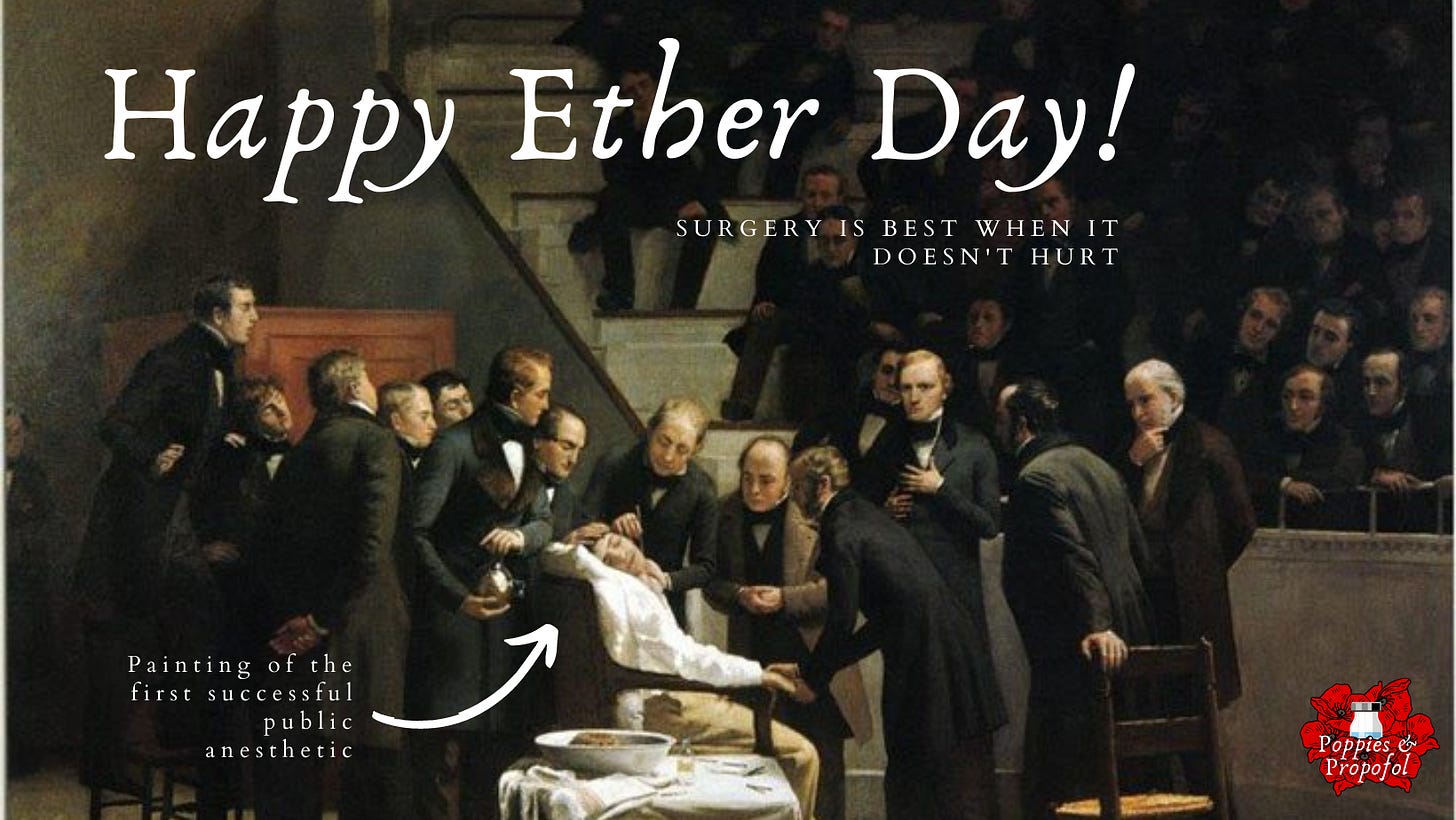

The idea that we needed a way to reduce the pain and consciousness during surgical interventions was on lot of people’s minds in the 1800s. Thankfully, a sizemic shift occurred on Monday, October 16, 1846, when an American dentist names William T. G. Morton publicly demonstrated the effectiveness of an anesthetic at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). The surgical theater at MGH is elevated in the hospital building, which ensured more natural light could illuminate the procedure, but also helped prevent the screams of people having surgery from overwhelming the entire hospital. But with the use of ethyl ether Edward Abbott, the patient, didn’t scream out once while a tumor was removed from his neck. It must have been a truly phenomenal to witness when all previous surgery had been performed in a room full of anxiety and screaming. I can only imagine the shift for the surgeon, John Collins Warren, MD, who would have been used to operating under the pressure of a patient expereincing excruciating pain. An era was ending in which people performing surgery would need to suppress the natural human responses to causing pain in other humans.

Another incredible anesthetic, nitrous oxide (also called laughing gas), was also coming of age within the same time period. A partner in Morton’s dental practice , Horace Wells, aimed to demonstrate the effectiveness of nitrous oxide for tooth extractions, but his public demonstration in 1845 was seen as a failure when the patient cried out in discomfort. The irony of Well’s unfortunate experience is that I still use nitrous oxide on a regular basis as a pediatric anesthesiologist, while ethyl ether has faded into anesthesia history.

Adam Rodman’s wonderful medical history podcast Bedside Rounds dedicates an entire episode to the Ether Dome. I highly recommend this episode (and the whole podcast!).

(There’s a boatload of historical drama, intrigue, lawsuits, and nonsense around this time in the history of anesthesia, and I’ll plan to get to it in future Poppies & Propofol writing.)

Please consider sharing with a friend. :)