Guilty Verdict for Former Nurse Won't Save Any Patients

Prosecuting healthcare workers who report errors will harm future patients

Welcome to Poppies & Popofol, a newsletter about bioethics and anesthesiology.

On Friday, March 25, 2022, former nurse RaDonda Vaught was convicted of gross neglect of an impaired adult and negligent homicide, for the death of a patient in 2017.

Medication errors can be deadly, and must be addressed with with the seriousness they deserve. But criminal prosecution of the former nurse will not save future patients - it will harm them.

Charlene Murphy’s Death was Preventable

A 75-year-old patient, Charlene Murphy, died at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in December 2017. Before discharging the patient home after a brain injury, the medical team ordered an PET scan (similar to an MRI) to assess her condition. The patient felt claustrophobic and a sedative was ordered to help her tolerate the scan, which slides the patient through a large donut-shaped tube.

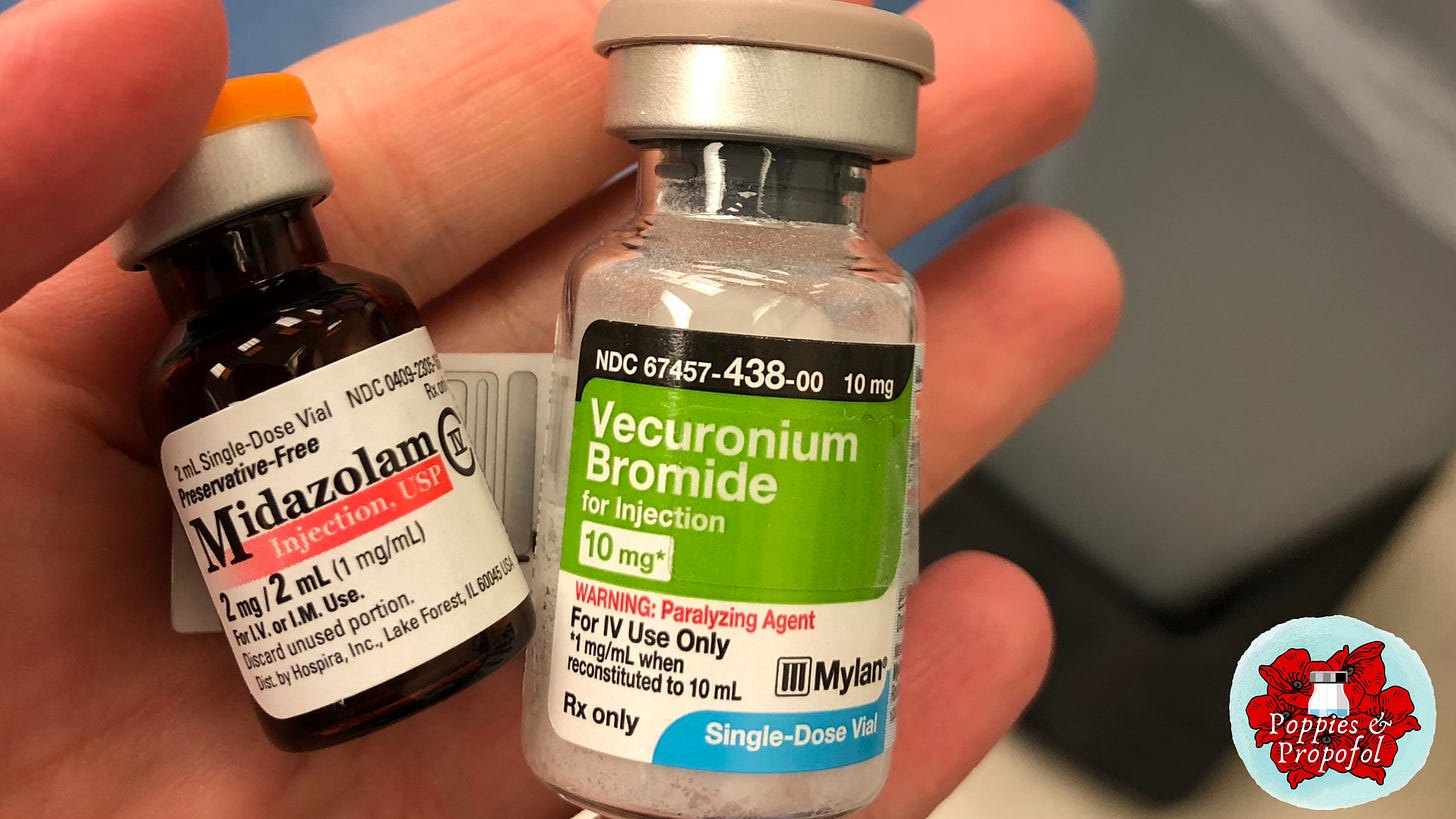

Instead of giving a sedative - a medication whose brand name is Versed (midazolam) - Ms. Vaught gave Mrs. Murphy vecuronium bromide. Vecuronium is a neuromuscular blocker - a medication that makes it so a patient’s muscles cannot contract. When this happens, patients remain awake, but unable to move - they are paralyzed. This is truly a patient’s worst nightmare, being paralyzed, dying, and unable to speak or defend oneself. Patients frequently bring up this common fear when discussing general anesthesia.

Of all potential fatal medication errors, paralyzing an awake patient and putting them in a scanner is among the worst. When I imagine what Mrs. Murray went through, I want to cry: she asked for a medication to sooth her anxiety, but instead received a medication that paralyzed her. She died from suffocation, aware of her condition until her brain had too little oxygen to remain conscious.

When I imagine what it must have been like to be RaDonda Vaught, I imagine the horror, disbelief, and shame she must have felt knowing her actions were against everything nurses stand for.

In the aftermath of Mrs. Murphy’s death, it was revealed the nurse had looked up the sedative in the electronic medication vending machine by its trade name, Versed, rather than its generic name, midazolam. By typing the first two letters in to the machine, she was given the option to dispense vecuronium. The system was not set up to also display trade names. There was no physician order for vecuronium, so the machine wouldn’t release it. The nurse did a “manual override” to get the machine to dispense what she believed was a sedative - this pushes the system to dispense a medicine over existing protections. The system was notorious for requiring frequent overrides for daily tasks, so the override itself didn’t trigger the nurse to reconsider what was dispensed.

As an anesthesiologist, I use both midazolam and neuromuscular blockers, like vecuronium, on a regular basis. There are a number of reasons why this mix-up, in particular, is simultaneously understandable and hard to fathom. These drugs are referred to as LASA drugs - Look-alike or sound-alike drugs. Based on the name alone, it’s not surprising that, combined with the pitfalls of the medication dispensing system, Vaught failed to notice the name difference in the dispensing screen. There are additional risks in medication administration when vials look the same. While vecuronium and Versed (midazolam), sound alike, do not look alike. Vecuronium generally comes in a larger clear vial, with numerous safety messages on it - a lid that says “Paralyzing Agent” and sometimes a little flag hanging off the vial with the same message. Midazolam is in a small, amber colored vial - and rarely says the trade name “Versed” on the bottle. Before drawing up and administering a medication, we are supposed to check that is is the correct medication for the correct patient, the correct dose, and that the medication is not expired.

The two drugs are also prepared very differently. Vecuronium is a white powder that should be diluted with 10 ml (milliliters) of water or saline to draw into a syringe. Midazolam is dispensed as a liquid - in this case, a 2 mg dose of midazolam is in 2 ml of clear liquid. For those of us who use vecuronium and other neuromuscular blockers regularly, it’s hard to imagine going to the trouble of reconstituting the medication without noticing the significant differences to midazolam. Ms. Vaught reported being in a hurry to sedate the anxious patient and being distracted as contributing factors to her grave error.

Don’t We Need Prosecution For Justice?

You may ask yourself, isn’t sending this nurse to jail a way to obtain justice for the dead? Won’t taking this nurse out of society improve patient safety? Doesn’t she deserve to go to jail?

The short answer is “no.”

Criminally prosecuting medical errors will actually damage the culture of safety, and harm future patients.

It’s been 22 years since the Institute of Medicine’s landmark report on medical errors, To Err is Human, was released. The report brought the risk of medical errors to the height of public attention and called for better systems to protect patients from the mistakes of their imperfect, human caregivers.

“To Err Is Human breaks the silence that has surrounded medical errors and their consequence--but not by pointing fingers at caring health care professionals who make honest mistakes. After all, to err is human. Instead, this book sets forth a national agenda--with state and local implications--for reducing medical errors and improving patient safety through the design of a safer health system.”

Every day I walk into the hospital, I could make an error that causes the death of a patient. Every nurse, pharmacist, anesthesiologist, and other healthcare worker who dispenses and delivers medications is at risk for this kind of event. If we’re honest with ourselves, each healthcare worker can look at RaDonda Vaught and see ourselves.

The verdict in this case will have a chilling effect on decades of quality improvement and patient safety efforts, especially in Tennessee where this case took place. Individual vigilance will never be enough to prevent all patient harm. Vigilance must be coupled with rigorous safety measures at every level. When we are punished for these errors, healthcare workers will hide them, and nothing can be learned or improved. Improving patient safety requires that healthcare workers feel they can safely report errors or lapses in judgement. These mistakes are then picked apart in the context of the larger system to figure out - how did this happen and how can we prevent it from ever happening again?

RaDonda Vaught reported her deadly error and admitted her role.

What nurse will feel safe doing the same now?

What about the system?

In the case of Mrs. Charlene Murphy, the former nurse seems to have taken all the criminal blame, despite the Vanderbilt hospital system’s many failings that contributed to this case. In addition to not creating a safer environment to prevent the error, Vanderbilt also failed to report the error and death to the appropriate oversight bodies - covering it up for ten months. Despite the conditions of her death, the patient’s death certificate recorded her cause of death as “natural.” This lack of reporting only became clear after it was anonymously reported to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Tennessee Department of Health.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) stated

“The real issue, in this case, is that there were no effective systems in place to prevent or detect the accidental selection, removal, and administration of a neuromuscular blocker that had been obtained via override.” The ISMP also calls for systems to lead a Just Culture and be accountable for designing safer hospitals, rather than pushing blame on individuals.”

Before the pandemic healthcare workers were burned out. Now we are more frazzled, distracted, and exhausted than ever before. Every year, our jobs increase in complexity. There seems to be continuous pressure to do more work with fewer resources. It takes immense bravery to be a healthcare provider under these conditions. And the past two years have only increased the risks.

Nursing associations, like the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, have released statements decrying the verdict.

Charlene Murphy’s death was horrible and preventable. RaDonda Vaught’s fatal error is something she will live with forever. But that error was not one individual’s fault. It took place in a complex health system with numerous contributing factors.

Prosecution will prevent healthcare workers from being honest about their mistakes. It won’t bring back Charlene Murphy, and it won’t prevent other deaths. It will hinder decades of effort to enhance patient safety.

Thanks for reading Poppies & Popofol, a newsletter about bioethics and anesthesiology. Please consider subscribing or sharing with a friend. ❤️😷💉